This morning, moments after I woke up, Kellie greeted me by saying, “It’s all over.”

“Huh?” I said, rubbing my eyes and starting the kettle.

“Our cabin,” she said, and explained that Aeneas Valley was evacuated overnight. Our cabin currently sits between two rapidly growing fires.

Just last weekend we had traveled there with a weed whacker in the back of the truck because the fire season was well under way, because it was already a bad one, because we were overdue for our annual fire abatement—and also, because we love it there.

We left on a Friday morning, the same morning that lightning had started dozens of small fires. Some of the fires had grown into big ones. As we drove through Chelan, the air grew increasingly thick with smoke. The parking lot of the elementary school was filled with fire trucks and mobilizing crews. Spectators lined up on one side of the bridge, shielding their eyes with their hands. As we crossed the bridge, I saw what they saw: a bright red fire descending down a not-so-distant hill.

We left on a Friday morning, the same morning that lightning had started dozens of small fires. Some of the fires had grown into big ones. As we drove through Chelan, the air grew increasingly thick with smoke. The parking lot of the elementary school was filled with fire trucks and mobilizing crews. Spectators lined up on one side of the bridge, shielding their eyes with their hands. As we crossed the bridge, I saw what they saw: a bright red fire descending down a not-so-distant hill.

For a mile we drove through smoke as thick as fog. When we finally turned North and traveled along the Columbia River, the air became suddenly clear enough that we could see again, and I felt just as suddenly that we had emerged from a place we shouldn’t have been. My sons pointed out the window, watching as a helicopter descended and filled its red bucket in the river. The bucket looked so small—like an overfilled water balloon—that I wondered how it was even worth the effort.

“That bucket carries 350 gallons,” Kellie told us. She speaks from experience. For nine years she fought fires on a helitack crew. Any time we hit the road during fire season, I can see something like nostalgia rise within her, a former way of being, woman vs. fire.

We traveled for another eighty miles, but the smoke never fully cleared. When we arrived at our cabin the air was visibly hazy. Kellie got out of her truck and surveyed the horizon. “That’s not good,” she said. She pointed to a puffy white cloud. It was mostly blocked by trees but steadily growing. Our kids ran wild around the cabin, but I stood there watching as Kellie narrated the cloud to me. There, where the cloud looked brown, living things were burning up. There, where white smoke fed the cloud, that fire was burning hot. I stood there transfixed. Without Kellie’s help I might not have even noticed that cloud, but now the more I looked the more I understood it as a living growing thing.

“Should we even stay?” I asked her. It was six o’clock already, and the sun would soon sink on the other side of the hills.

“It will cool down tonight,” Kellie said. “We’ll watch it in the morning.”

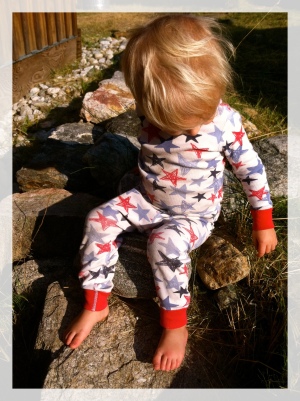

I spent the night awake, imagining the fire creeping towards us, the phrase “fast as wildfire” in my head, but when morning came our land was magically clear and still. Stump, our two-year-old son, played on the porch while I drank my morning tea at the picnic table. My heart filled. Usually being in wilderness feels good, but there’s angst at the edges. It’s a little too hot or a little too cold, or you’re swatting away at black flies, or your kids are fighting, or one of your dogs keeps putting his nose in your crotch. But this morning the sky was blue and the air was just cool enough. The smoke had settled. The fire clouds from yesterday had disappeared.

Kellie spent the day whacking down dry grass and raking it into piles. Together we moved the piles to a tarp and dragged them away from the cabin. Every year we had done this. The idea is to create a safe un-flammable circle around the cabin, but to be honest it feels more like dropping a penny in a well.

Kellie spent the day whacking down dry grass and raking it into piles. Together we moved the piles to a tarp and dragged them away from the cabin. Every year we had done this. The idea is to create a safe un-flammable circle around the cabin, but to be honest it feels more like dropping a penny in a well.

That evening Kellie said to me, “If there’s anything you want to save, now’s the time to grab it.” It took me a minute to realize what she meant. She meant that even though the air looked clear right now, even though I had relaxed my guard, I should prepare to say goodbye. I should save any object I wanted to keep. Kellie pointed to a painting of a mountain goat we’d found at a thrift store, and an antique wooden goblet that featured an elk. These were her choices. I agreed with them.

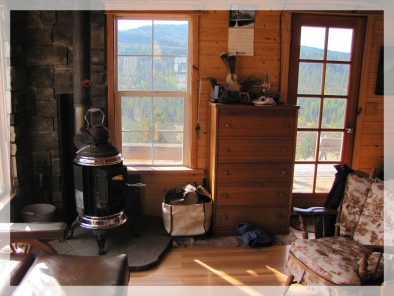

Only two weeks ago, I wrote about object attachment and how, if you asked me what three things I would save from a fire I wouldn’t know what to choose. As it turns out, that was accurate. As I looked around the cabin, the things that I wanted to save were the walls, the floor, the woodstove, the porch. The actual cabin. There wasn’t any individual thing I wanted, just all of things, together.

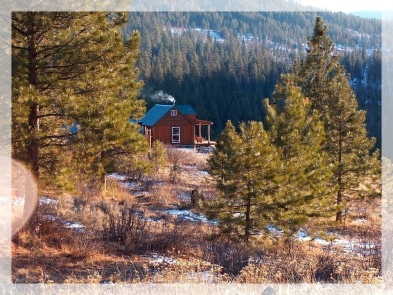

Earlier in the day it had occurred to me: this cabin was the one thing that Kellie and I have bought and made together. Kellie and I had been a couple for three years when we decided to buy raw land. We spent months driving around the state every weekend looking at parcels. We bought land where we did because it was cheap and wild and beautiful, even though it meant driving three hundred miles on the highway and another six miles up a rutted dirt road. We paid a local jack-of-all-trades to build a cabin: four walls and a loft and some windows. We’d do all the finish work ourselves.

For at least three years we spent seasons full of weekends making that drive to put in floors, build an outhouse, install a deck. I’m not handy, but I can follow directions and Kellie can give them, and so when I look at the floors I remember installing the boards with a pry bar and a nail gun, and when I look at the ceilings I remember trying to hold the sheets of plywood steady, one at a time, while Kellie nailed them to the beams.

We were probably halfway through this years-long project when Kellie and I got married in front of family and friends, but when I look back on things it feels like that cabin is the thing that married us. Because driving six hundred miles together every weekend, and drinking beers on the front porch as the sun sunk below the hills, and arguing about whether or not that board is hung at an angle, and trading off two-minute solar showers, those are the things that bound us.

On Sunday afternoon, the day before we had planned to leave, we drove eight miles to the general store for ice cream. As we pulled into the dirt parking lot there were people watching the most recent blaze. The fire was climbing up one side of the hill, and it was clear that soon it would descend on the other side. The store owner said he would stay open all night. Further in the distance was another fire cloud. These two fires were expected to combine and grow. A couple in a Subaru pulled in next to us as we watched the fire and ate our ice cream.

On Sunday afternoon, the day before we had planned to leave, we drove eight miles to the general store for ice cream. As we pulled into the dirt parking lot there were people watching the most recent blaze. The fire was climbing up one side of the hill, and it was clear that soon it would descend on the other side. The store owner said he would stay open all night. Further in the distance was another fire cloud. These two fires were expected to combine and grow. A couple in a Subaru pulled in next to us as we watched the fire and ate our ice cream.

“Is anyone fighting that?” a tall man in his thirties asked Kellie.

“There’s no one left to fight it,” Kellie said. “The whole west is on fire.” We watched as a single airplane zigzagged in the distance, but so far there was no parade of fire trucks, no clear and obvious rally like what we’d seen in Chelan.

That night I took a bath outside as the clouds changed color and I felt as lucky as I ever have to be nestled, naked, in the mountains. Though I knew that fires blazed less than ten miles away, the air was clear and it was easy to believe that all was well, that it always had been and it always would be.

That night I took a bath outside as the clouds changed color and I felt as lucky as I ever have to be nestled, naked, in the mountains. Though I knew that fires blazed less than ten miles away, the air was clear and it was easy to believe that all was well, that it always had been and it always would be.

This morning, after Kellie shared the news about the evacuation and the growing fire, as I slowly woke up and tried to believe what I knew was real, I thought about our cabin floors again, and our walls. From the beginning we knew that we risked losing anything we built on that mountain, that wild fires blazed every year and missing them was just a matter of luck. Still, we didn’t build a cabin we could bear to lose. We built it as if we planned to pass it on to our sons, to keep it in our family forever. We loved every beam and every plank. We cut our pieces carefully and laid them out true. And I realize that is exactly how I want to live.

Reblogged this on Jdawgswords and commented:

my thoughts and prayers to all those threaten/affected by the western states fires

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry to hear about this. Stay Safe

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an amazing cabin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is an amazing piece of land and what I agree with you most about is that it IS the ideal way to live. A cabin in the mountains is my ideal home. Not the suburbs or city. Keeping my thoughts with you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Beautifully written. My thoughts and prayers are with you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It must be torture knowing you may or may not lose your house that you obviously love. Plus, out of control wildfires are the last thing our state needs right now. We don’t need to be wasting water putting out wildfires, but we must. I hope you stay safe and I’ll pray for you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Looks like we get to keep our cabin and our spot for now. Thanks for the kind words and thoughts!

LikeLike

Fires are so bad. Praying for all those affected. I live in Idaho where the Soda Fire just consumed almost 300,000 acres. So many homes, farms, wildlife and dreams burnt to ashes. So sad.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Dreams burned to ashes”–so true. I’ll be thinking of those in your state as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on aryanchaurasia.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A trip and a story is so exciting

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope your cabin remains in tact. I live in oregon as well and have dealt with fires here, they are all over. So.e recently near where my daughters live with their dad up the Santiam pass. It’s been a bad year. Thankfully as i type this it’s down pouring. I sure hope it helps with those areas that really need it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hooray for rain. We’ve got some cooler weather slowing things down here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree wholeheartedly!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Captivating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am so sorry for your loss … I can’t even imagine what you both are going through. I live in Everett and I love that area and am so sad it’s on fire. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That looks preaty bad

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish to have a cabin like this in the woods.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh no. I’m so sorry!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully written, I hope all is well at you cabin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on ishal23.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow

LikeLiked by 1 person

So sorry

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like the picture,and hope u have a nice day!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sending prayers from Canada.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful story. Beautiful cabin. Just beautiful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

When we built our 10×12 on five acres here in NorCal, we knew like you it could go up in smoke. We built it simple and furnished it with junk. We finally insulated our outhouse – woo woo! Diamond Jim Brady!

But I won’t lie – if it burned down tomorrow I’d be in shock. It’s not just a vacation place to us it’s our sanctuary.

I’m not religious, but I am a total paranoid – I went out and bought a ceramic statue of St. Francis and had my son build a little house for him and we mounted him in a tree at the front gate.

today, on a more practical note, I will be up there with my pitchfork and my loppers doing fire clearance with my neighbors, hoping the best for you and yours, Hillbilly Woman. When I’m up there raking, I look down that cliff, and I know that fire would come at us like a blow torch! But I keep raking and whacking, it’s something.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good writing skill

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel so bad for the people who lose everything. I have been there I know how it feels not to have anything left.

LikeLiked by 1 person